Photo by Dietrich Gesk

Photo by Dietrich Gesk Minneapolis-based jazz pianist, composer and teacher, Mary Louise Knutson has toured all over the United States with former Tonight Show bandleader and trumpeter Doc Severinsen and his big band and with her own group the Mary Louise Knutson Trio. She has appeared with such jazz greats as Dizzy Gillespie, Bobby McFerrin, Dianne Reeves, Kevin Mahogany, and many others. As a show player, Knutson has performed with artists such as Reba McEntire, Michael Bolton, Donny Osmond, Smoky Robinson, the Osmond Brothers and comedian Phyllis Diller. Knutson's latest jazz trio CD, In the Bubble, made JazzWeek's Top 10 and stayed in the Top 50 for 19 consecutive weeks. Knutson's debut jazz trio CD, Call Me When You Get There, was featured in JazzWeek's Top 50 for eight consecutive weeks, earning Knutson the award for “Top New Jazz Instrumentalist of the Year” in 2001 from KWJL Radio in California. In 2006 Knutson was a Minnesota Music Awards nominee for both Jazz Artist of the Year and Pianist of the Year, and in 2005, she was a Finalist in the Kennedy Center’s Mary Lou Williams "Women in Jazz" International Pianist Competition. In 2004, Knutson was the recipient of Lawrence University's distinguished Nathan M. Pusey Alumni Achievement Award. As a composer she has won numerous awards, including two from Billboard magazine. Formerly an instructor in jazz piano and improvisation at Carleton College, Knutson teaches privately and conducts master classes in jazz, composition and improvisation.

Lisa: As I listened to your CDs Call Me When You Get There and In the Bubble, I was struck by the lyricism and line in your music, both as a pianist and a composer. We pianists have a challenge playing an instrument that creates sound through a percussive hammer on a string and trying to make that sound like singing! How do you achieve that?

Mary Louise: Thanks for noticing that, Lisa! Playing and writing lyrically are very important to me. In addition to my 18 years of classical piano training (where lyrical playing was emphasized), I sang in choirs in high school, more choirs and a jazz vocal group in college, and then when I finally went out into the world as a jazz pianist, I sang and accompanied myself on my gigs. After a couple years of this, people started referring to me as a singer, not a pianist. I didn't like that because I had always identified myself as a pianist. I was jealous that the singer part of me was getting more attention than the pianist part of me who had been there so much longer and had worked so much harder to hone her skills. So, I decided to stop singing and give full attention to my piano playing. Perhaps my voice would have attracted more gigs in the long run, but my desire to express myself through the piano and to be identified as a pianist won out. I really do sing inside my head when I play and I'm glad that people can hear that coming through in my music.

Lisa: How do you teach students to play lyrically?

Mary Louise: To play a jazz or popular song melody more lyrically, or with more style, I teach students to sing the line and notice where their voice scoops or falls into the pitches. Wherever that happens I tell them to imitate it on the piano by scooping or falling into the pitch from a couple notes below or above the pitch. Singing is always helpful as it provides an internal experience for something we are trying to reproduce externally. Also, students can enhance the shape of lines by crescendoing when the melody rises and decrescendoing when the melody falls. When addressing lyricism in improvisation or composition, I emphasize the importance of balancing the combination of steps, skips, and leaps, and tensions vs. releases.

Lisa: Many classical musicians are afraid of improvisation, and lay people are intimidated by the whole notion of playing and performing. What stands in the way of experimenting?

Mary Louise: What stands in the way of experimenting is often fear of the unknown, fear of sounding "bad," and self-judgment. I had plenty of fear and self-judgment when I first started improvising. Like most classical students, I was rooted in reading what was on the page. I played music by sight. So, when I tried improvising as a college student, I was told to follow where my ear was leading me. But my ear wasn't leading me anywhere. It wasn't prompting me with any musical ideas. So I just pressed down random keys and found that just about everything I played sounded bad. Being a person who had previously only played composed music, I was used to the music sounding "good" or "right", so sounding “bad” made me very uncomfortable. Slower tempos made things slightly easier, but most everything was a struggle. Mind you, I was also doing this in front of my peers, many of whom were already experienced improvisers. So I felt judged and I judged myself. That set up a cycle of fear and disappointment around the whole topic of improvisation. But I loved the sound of jazz and really wanted to learn how to improvise, so I kept on trying.

Lisa: How did you ultimately learn to improvise?

Mary Louise: What I learned is that I needed to develop my vocabulary. Jazz, pop, rock, folk, country, latin, and blues are all languages that have their own specific style of vocabulary. And just as a young child needs to build their vocabulary in order to speak their native language, or as people need to do in order to learn a foreign language, musicians need to learn the vocabulary of their chosen genre of music in order to improvise. Musical vocabulary comes in the form of scales, chords, licks, riffs, rhythms, articulations, tunes, etc. And once internalized, the vocabulary is linked together to make musical sentences and paragraphs. In our spoken language, we improvise every day in our conversations with each other. We don't plan out what we're going to say. With our vocabulary and knowledge on many topics, we improvise in the moment and just say what's on our mind. And so, in music, to speak spontaneously (improvise) and say what's on our mind, we need to develop our vocabulary.

Lisa: How can we teach our students to improvise?

Mary Louise: To help students become more comfortable with experimenting and improvising, I have them work with some vocabulary they already know - the C Major scale. I play a chord progression that perfectly compliments the C Major scale (||: Cmaj7 | Am7 | Dm7 | G7 :|| in 4/4 with an eighth-note subdivision). Then, I ask the student to noodle around in quarter-notes or eighth-notes on the C Major scale with their right hand along with my accompaniment. Most students will have instant success in terms of sounding "good" or "right," and this builds their excitement. Then I show them the chord progression so they can play it at home with their left hand, and the right hand improvises again with the C Major scale. If students internalize (memorize) the C scale and the chord progression, these will be their first two learned "vocabulary words," and they'll be ready to play a simple improvisation at any moment for themselves or for their friends. If they learn more vocabulary, they'll have more tools to express themselves. Many professional jazz musicians learn much of their vocabulary in all 12 keys so they're prepared to improvise in any context that might present itself.

Lisa: What is the most important thing young pianists and composers need to know?

Mary Louise: They need to know that learning to play an instrument or to compose music requires a lot of patience. Unfortunately, today's world does not teach us patience. It teaches us impatience. Information is provided so quickly through computers that we've all become incapable of waiting for anything that requires a longer process. So, when it comes to learning an art form (something that requires a longer process), students are often surprised by the amount of time it takes to accomplish their goals and they give up too quickly. They can't imagine why anything could possibly take so long to learn. Or they mistake their slow progress as a lack of talent. Truly, they just lack patience - patience to put some time in on their instrument or their composing every day. Some days they'll feel like no progress was made, and other days there will be leaps and bounds. But progress will happen with consistent effort. In my 40-something years of practicing and composing I've had many periods of impatience and have wondered many times whether it is all worth the effort. But luckily, I've remembered to be patient with myself and with the process - that I accomplish the most when I'm consistently putting time into my practicing or composing. Giving consistent attention to your art will bring you great accomplishment and deep satisfaction, as well as boost your self-esteem. Plus, if you learn patience now, you'll have a valuable tool for many, if not all, of life's challenges.

Lisa: That sounds like great advice! What is the wisest thing anyone ever told you?

Mary Louise: Jazz pianist Bill Carrothers once told me, "People judge you by your actions, not your intentions." I was taking a lesson from him at the time, during the late 90s. At the time, I had intended to do a lot of wonderful things at some point in my life (like recording and performing my own music), but had taken very little action. I was living in a comfortable and safe world of dreams. There, I could visualize the great things I would do without being subject to the world's criticisms. But, I was also sheltering myself from the world's praises and various opportunities that would result from people getting to know me. So Bill's statement lit a fire under me to take a risk and take some action.

Lisa: Any last words?

Mary Louise: Thank you all, and Lisa (our host), for the opportunity to share my thoughts with you. Here's wishing you all joyful adventures in music!

To learn Mary Louise Knutson's ideas on jazz, improvisation, composition and creativity visit http://myrestlessmuse.blogspot.com/

To purchase CDs or learn about Mary Louise Knutson's upcoming performances and master classes visit her website: http://www.marylouiseknutson.com/default.htm

Lisa: As I listened to your CDs Call Me When You Get There and In the Bubble, I was struck by the lyricism and line in your music, both as a pianist and a composer. We pianists have a challenge playing an instrument that creates sound through a percussive hammer on a string and trying to make that sound like singing! How do you achieve that?

Mary Louise: Thanks for noticing that, Lisa! Playing and writing lyrically are very important to me. In addition to my 18 years of classical piano training (where lyrical playing was emphasized), I sang in choirs in high school, more choirs and a jazz vocal group in college, and then when I finally went out into the world as a jazz pianist, I sang and accompanied myself on my gigs. After a couple years of this, people started referring to me as a singer, not a pianist. I didn't like that because I had always identified myself as a pianist. I was jealous that the singer part of me was getting more attention than the pianist part of me who had been there so much longer and had worked so much harder to hone her skills. So, I decided to stop singing and give full attention to my piano playing. Perhaps my voice would have attracted more gigs in the long run, but my desire to express myself through the piano and to be identified as a pianist won out. I really do sing inside my head when I play and I'm glad that people can hear that coming through in my music.

Lisa: How do you teach students to play lyrically?

Mary Louise: To play a jazz or popular song melody more lyrically, or with more style, I teach students to sing the line and notice where their voice scoops or falls into the pitches. Wherever that happens I tell them to imitate it on the piano by scooping or falling into the pitch from a couple notes below or above the pitch. Singing is always helpful as it provides an internal experience for something we are trying to reproduce externally. Also, students can enhance the shape of lines by crescendoing when the melody rises and decrescendoing when the melody falls. When addressing lyricism in improvisation or composition, I emphasize the importance of balancing the combination of steps, skips, and leaps, and tensions vs. releases.

Lisa: Many classical musicians are afraid of improvisation, and lay people are intimidated by the whole notion of playing and performing. What stands in the way of experimenting?

Mary Louise: What stands in the way of experimenting is often fear of the unknown, fear of sounding "bad," and self-judgment. I had plenty of fear and self-judgment when I first started improvising. Like most classical students, I was rooted in reading what was on the page. I played music by sight. So, when I tried improvising as a college student, I was told to follow where my ear was leading me. But my ear wasn't leading me anywhere. It wasn't prompting me with any musical ideas. So I just pressed down random keys and found that just about everything I played sounded bad. Being a person who had previously only played composed music, I was used to the music sounding "good" or "right", so sounding “bad” made me very uncomfortable. Slower tempos made things slightly easier, but most everything was a struggle. Mind you, I was also doing this in front of my peers, many of whom were already experienced improvisers. So I felt judged and I judged myself. That set up a cycle of fear and disappointment around the whole topic of improvisation. But I loved the sound of jazz and really wanted to learn how to improvise, so I kept on trying.

Lisa: How did you ultimately learn to improvise?

Mary Louise: What I learned is that I needed to develop my vocabulary. Jazz, pop, rock, folk, country, latin, and blues are all languages that have their own specific style of vocabulary. And just as a young child needs to build their vocabulary in order to speak their native language, or as people need to do in order to learn a foreign language, musicians need to learn the vocabulary of their chosen genre of music in order to improvise. Musical vocabulary comes in the form of scales, chords, licks, riffs, rhythms, articulations, tunes, etc. And once internalized, the vocabulary is linked together to make musical sentences and paragraphs. In our spoken language, we improvise every day in our conversations with each other. We don't plan out what we're going to say. With our vocabulary and knowledge on many topics, we improvise in the moment and just say what's on our mind. And so, in music, to speak spontaneously (improvise) and say what's on our mind, we need to develop our vocabulary.

Lisa: How can we teach our students to improvise?

Mary Louise: To help students become more comfortable with experimenting and improvising, I have them work with some vocabulary they already know - the C Major scale. I play a chord progression that perfectly compliments the C Major scale (||: Cmaj7 | Am7 | Dm7 | G7 :|| in 4/4 with an eighth-note subdivision). Then, I ask the student to noodle around in quarter-notes or eighth-notes on the C Major scale with their right hand along with my accompaniment. Most students will have instant success in terms of sounding "good" or "right," and this builds their excitement. Then I show them the chord progression so they can play it at home with their left hand, and the right hand improvises again with the C Major scale. If students internalize (memorize) the C scale and the chord progression, these will be their first two learned "vocabulary words," and they'll be ready to play a simple improvisation at any moment for themselves or for their friends. If they learn more vocabulary, they'll have more tools to express themselves. Many professional jazz musicians learn much of their vocabulary in all 12 keys so they're prepared to improvise in any context that might present itself.

Lisa: What is the most important thing young pianists and composers need to know?

Mary Louise: They need to know that learning to play an instrument or to compose music requires a lot of patience. Unfortunately, today's world does not teach us patience. It teaches us impatience. Information is provided so quickly through computers that we've all become incapable of waiting for anything that requires a longer process. So, when it comes to learning an art form (something that requires a longer process), students are often surprised by the amount of time it takes to accomplish their goals and they give up too quickly. They can't imagine why anything could possibly take so long to learn. Or they mistake their slow progress as a lack of talent. Truly, they just lack patience - patience to put some time in on their instrument or their composing every day. Some days they'll feel like no progress was made, and other days there will be leaps and bounds. But progress will happen with consistent effort. In my 40-something years of practicing and composing I've had many periods of impatience and have wondered many times whether it is all worth the effort. But luckily, I've remembered to be patient with myself and with the process - that I accomplish the most when I'm consistently putting time into my practicing or composing. Giving consistent attention to your art will bring you great accomplishment and deep satisfaction, as well as boost your self-esteem. Plus, if you learn patience now, you'll have a valuable tool for many, if not all, of life's challenges.

Lisa: That sounds like great advice! What is the wisest thing anyone ever told you?

Mary Louise: Jazz pianist Bill Carrothers once told me, "People judge you by your actions, not your intentions." I was taking a lesson from him at the time, during the late 90s. At the time, I had intended to do a lot of wonderful things at some point in my life (like recording and performing my own music), but had taken very little action. I was living in a comfortable and safe world of dreams. There, I could visualize the great things I would do without being subject to the world's criticisms. But, I was also sheltering myself from the world's praises and various opportunities that would result from people getting to know me. So Bill's statement lit a fire under me to take a risk and take some action.

Lisa: Any last words?

Mary Louise: Thank you all, and Lisa (our host), for the opportunity to share my thoughts with you. Here's wishing you all joyful adventures in music!

To learn Mary Louise Knutson's ideas on jazz, improvisation, composition and creativity visit http://myrestlessmuse.blogspot.com/

To purchase CDs or learn about Mary Louise Knutson's upcoming performances and master classes visit her website: http://www.marylouiseknutson.com/default.htm

Album Cover Photo by Dietrich Gesk

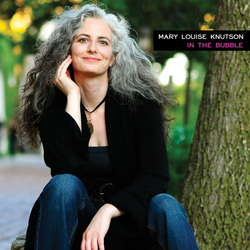

Album Cover Photo by Dietrich Gesk In the Bubble:

"This is timeless, classic piano trio music, right up there with Bill Evans and Bill Charlap."

-Pamela Espeland, from Twin Cities Critics Tally 2011: Top 10 Albums, Twin Cities Star Tribune

"...a masterful combination of original works and new arrangements... Knutson's compositions are marked by exquisite melodies, emotive harmonies, shifting rhythms and an elegant touch that recalls McPartland, Arriale, and Jarrett." -Andrea Canter, JazzINK.com

"Swinging and wonderful...In the Bubble is my pleasant surprise of the day. I love it."

-Judy Carmichael, radio host, Judy Carmichael's Jazz Inspired, XM and Sirius Satellite, Channel 122, NYC

Check out these samples from IN THE BUBBLE:

CDBaby http://www.cdbaby.com/cd/marylouiseknutson

Amazon http://amzn.to/1fCGmyc

iTunes https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/in-the-bubble/id475772283

"This is timeless, classic piano trio music, right up there with Bill Evans and Bill Charlap."

-Pamela Espeland, from Twin Cities Critics Tally 2011: Top 10 Albums, Twin Cities Star Tribune

"...a masterful combination of original works and new arrangements... Knutson's compositions are marked by exquisite melodies, emotive harmonies, shifting rhythms and an elegant touch that recalls McPartland, Arriale, and Jarrett." -Andrea Canter, JazzINK.com

"Swinging and wonderful...In the Bubble is my pleasant surprise of the day. I love it."

-Judy Carmichael, radio host, Judy Carmichael's Jazz Inspired, XM and Sirius Satellite, Channel 122, NYC

Check out these samples from IN THE BUBBLE:

CDBaby http://www.cdbaby.com/cd/marylouiseknutson

Amazon http://amzn.to/1fCGmyc

iTunes https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/in-the-bubble/id475772283

Album Cover Photo by Dietrich Gesk

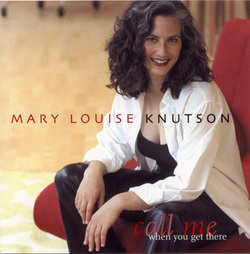

Album Cover Photo by Dietrich Gesk Call Me When You Get There:

"Call Me When You Get There is...state-of-the-art piano trio finery."

-JazzTimes

"...an excellent pianist whose voicings sometimes recall Bill Evans...she has a talent for coming up with fresh melodies. This is an impressive disc..."

-Scott Yanow, LA Jazz Scene

"Listening to Knutson's signature piece is like eating chocolate mousse; smooth, rich and filling. Yumm." -Bob Friedman, Fan

Listen to samples of Call Me When You Get There at:

CDBaby http://www.cdbaby.com/cd/Knutson

Amazon http://amzn.to/1lv162U

iTunes https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/call-me-when-you-get-there/id14869805

"Call Me When You Get There is...state-of-the-art piano trio finery."

-JazzTimes

"...an excellent pianist whose voicings sometimes recall Bill Evans...she has a talent for coming up with fresh melodies. This is an impressive disc..."

-Scott Yanow, LA Jazz Scene

"Listening to Knutson's signature piece is like eating chocolate mousse; smooth, rich and filling. Yumm." -Bob Friedman, Fan

Listen to samples of Call Me When You Get There at:

CDBaby http://www.cdbaby.com/cd/Knutson

Amazon http://amzn.to/1lv162U

iTunes https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/call-me-when-you-get-there/id14869805

RSS Feed

RSS Feed